A politician famous for his good character and high ideals?

It's rare now, and it was was rare back in the mid-nineteenth century, too. That might be one of the reasons why, when William A. Wheeler was chosen as Rutherford B. Hayes' running mate in the election of 1876, not too many people had heard of him.

As a famous story goes, when it was suggested to Rutherford B. Hayes that his running mate would end up being William Wheeler, the then-governor wrote to his wife, "I am ashamed to say, who is Wheeler?"

No one in the North Country of the time would say that. He was the "New York Lincoln." A towering figure in business, one of the creators of the Adirondack and Niagra Falls state parks, expander of civil rights, key founder of the modern Republican Party, and then the nation's 19th Vice President.

Yet he was humble and self-effacing, a devoted husband and low-key power broker who let no ripple of scandal mar his reputation. This very lack of controversy might have contributed, then and now, to his low profile.

difficult beginnings

William Almon Wheeler was born in Malone on June 30, 1819. He was the third child, and first son, of Almon Wheeler and Elizabeth (Woodworth) Wheeler. William began life rather well, with his father convincing the town to grant him legal privileges -- despite his years of study being short of the usual requirements, and then being appointed Malone Postmaster. Young "Bill," as he was known, was seven when his father took suddenly ill and died.

His mother was known as a "commanding figure" of a woman, with keen black eyes and a strong-minded character. But now, with two teen girls and a little boy to raise, she needed help. She was able to enlist the Reverend Ashbel Parmalee of the Congregational Church, a fervent Abolitionist, and Asa Hascall, prominent District Attorney, as surrogate fathers.

While his mind and character were in good hands, money was scarce. Young Bill once got the offer of "all the fallen timber he could haul" from a lot a mile north of the family home. All by himself, he chopped and hauled enough wood to keep the family in stovewood for a year. To get Bill through high school, his mother took in student boarders. To get Bill into the University of Vermont, a mysterious financial donator (rumored to be "Uncle" Hascall) loaned him enough money to enroll.

Bill received many gifts from his studies there. It was the first college in the United States to establish an English Literature department, and Bill was to enthusiastically use such knowledge to enhance his speeches and his reputation as a gentleman of cultured tastes. Even more practical use were the many clubs on campus which employed parliamentary procedure. This specialized knowledge would come into play with Bill's celebrated ability to shepherd legislation through a minefield of procedural rules.

Still, money continued to be a challenge, and at the age of twenty one, Bill dropped out to study law with his Uncle Hascall, completing in four years instead of the usual seven. He managed to be appointed town clerk and also acquired a district teaching post. From this more secure position he was able to court, and win, the hand of Mary King, daughter of a prominent local businessman. With marriage, in 1845, came a "modest fortune" from his new father-in-law.

The future, finally, began to look bright.

rise to prominence

It started with a bridge.

There had been strong popular support for a railroad bridge across Lake Champlain, as a boon to travel and commerce. Yet this important structure had been blocked by areas of the state which did not want to lose Canal business by seeing an alternative appear. By emphasizing progress, and marshaling support from hometown businesses who would reap the benefits of expanded railroad access, Bill garnered professional accolades and local gratitude.

These same tactics would turn out to be a winning combination for Bill as he and Mary moved back and forth from Albany to Washington DC, from the home they always kept in Malone, to a boardinghouse in the nation's capital where they became known for their lovely singing voices, raised in tuneful worship.

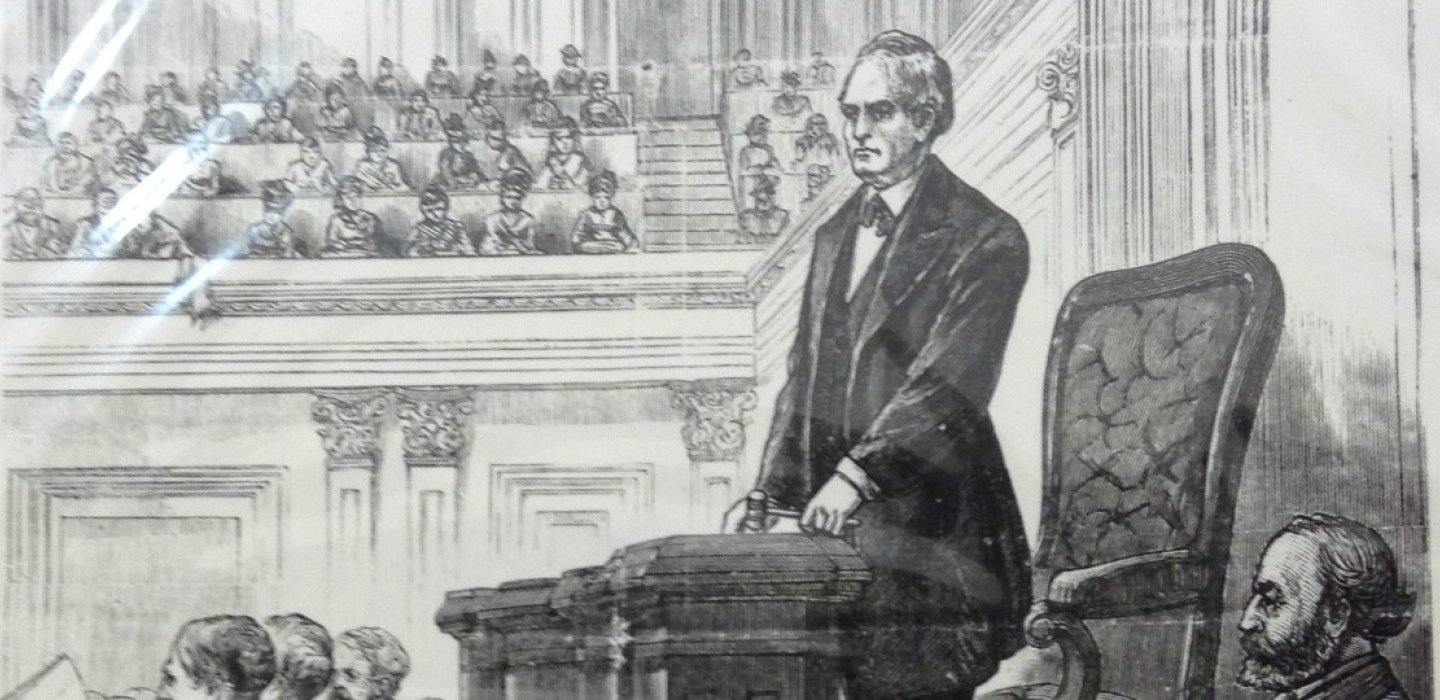

As President of the New York State Constitutional Convention in 1867, Bill's acceptance speech was an extraordinary endorsement of equal rights that was ahead of his time:

"We owe it to the cause of universal civil liberty, we owe it to the struggling liberalism of the old world,...that every man within [New York], of whatever race or color, or however poor, helpless, or lowly he may be, in virtue of his manhood, is entitled to the full employment of every right appertaining to the most exalted citizenship."

Unlike many political figures of the time, Bill's commitment to civil rights for African American citizens was heartfelt. In 1874, during the November elections in Louisiana, there were violent clashes between newly enfranchised black voters and long-time white voters. Bill was one of seven appointed by Congress to investigate the situation. While he was not the leader of the delegation, he was the author of a compromise both political parties could agree to.

What could have been a violent and difficult confrontation resulted in peaceful gains for both sides. William Wheeler might not have been famous among voters in the nation, but among the movers-and-shakers of both political parties, he was becoming increasingly known, and respected.

even higher office

William Almon Wheeler once said that the greatest trial of being vice president was that when he attended church:

"I hear the minister praying for the President, his Cabinet, both Houses of Congress, the Supreme Court, the governors and legislatures of all the states and every individual heathen . . . and find myself wholly left out."

This was to be Bill's fate -- despite a wholly-normal appetite for power as befitted a politician, his very integrity would have a tendency to hold him back.

He was exploring the national appetite for him to be nominated for President, and doing very well, when his beloved Mary suddenly passed away. Her illness had not seemed serious, and she was even on the mend. This loss was devastating to Bill. He immediately lost all interest in higher office.

Even without his participation, the "Wheeler for President" campaign was notable for its continued life. The upcoming political convention would be decisive about what role he would continue to play, but Bill was so lacking in energy to determine his fate that he went to the Adirondacks instead. His plans were to go fishing, one of his favorite pastimes.

From there, he journeyed to West Point, as part of his responsibilities for overseeing the military college. He didn't even attend the convention, and even so, it took five deeply contested ballots for a break to come. But it was not for Bill. It was for Rutherford B. Hayes, who prevailed by the seventh ballot. Wheeler's prominence was such that he was carried along to the Vice Presidency.

A telegram bearing the news appeared at his brother-in-law's home in Garrison, New York, where he was staying. If only a few key states had broken his way, he might have prevailed. Typically of him, Bill did not complain about his second place showing. He told his friends, "God's hand is in this work."

Unlike today, nineteenth century campaign practices did not ask too much of the candidates. Bill wrote a formal letter accepting his candidacy and gave a mere handful of speeches in strategic areas. The rest was supposed to be left up to the party faithful in each state. Hayes attempted to entice Bill into making speeches instead of him, but Bill cited his own poor health as a reason to decline.

On Election Night, when Bill realized he had lost New York, he was certain the Hayes-Wheeler ticket would not prevail. Newspapers blared headlines celebrating their rivals as the victors. Still, at Party Headquarters, vote counting went very slowly in these pre-computer times. There was considerable controversy, claims of illegal counting, and legal challenges throughout the states. Between December 6, 1876, when the Electoral College cast their votes, and March 4, 1877, Inauguration Day, a possible Constitutional Crisis loomed.

The principled decision of one of the appointed judges to withdraw from the electoral commission suddenly shifted the balance to the party of Hayes and Wheeler. The defeated party planned to mount a filibuster in the house. Only a last-minute compromise by Hayes, making concessions to some of the most hotly debated issues of the campaign, brought about a smooth transition of power.

At the age of fity seven, William Wheeler was a "heartbeat away" from the Presidency.

Hayes had made a campaign promise to not run again, and he kept it. Wheeler would have been a serious contender for the nomination, except political infighting had fractured his support in his home state of New York. Wheeler made private plans to run for the US Senate, instead, while not discouraging any Presidential talk, which could only help his campaign.

But his ambitions would not be realized. Vicious infighting among the party, a key suicide, and then President Garfield's assassination would all conspire to bring Wheeler's political career to a close. Declining health precluded him from being influential on the national stage again. The end came in 1887, after a lingering illness. He was laid to rest in Malone, next to Mary.

He was one of a kind.

Find some Malone lodging. Explore our hometown dining. Discover our many attractions.

Black and white photos courtesy of Franklin County Historical and Museum Society.

In related Fame In The ADKs news:

No joke. Will Rogers has seen its fair share of famous entertainers.

A star-studded past with more stars on the horizon.

Lighting the way for the rich and famous.

Comments

Add new comment